In a world with a changing climate, how we design our homes matters.

Reduced environmental impact has long been a huge focus of green building. Yet our homes are also critical in protecting us from the environment when that environment turns harsh.

As it turns out, some of the most basic principles in sustainable building also greatly improve resilience to changing and strengthening natural disasters, both on the level of our individual shelters and of entire communities. Resilience, in turn, tends to decrease a building’s environmental footprint. After all, a home that is constantly rebuilt is far from environmentally responsible.

Here are four basic principles from the world of sustainable building that also improve resiliency.

- Insulate and seal the building envelope

This is the single most important strategy advocated by building scientists and green-building experts to reduce a home’s energy use. A home with high levels of insulation and good windows, and one that is extraordinarily air tight, can have half the heating and cooling costs of the same home with average features.

Since heating and cooling is the largest energy expenditure of most homes, since insulation and air-sealing are very cost-effective, and since the energy consumed by residences contributes 20 percent of equivalent national carbon emissions according to the U.S. Energy Information Agency, it makes sense that this strategy would rise to the top of the list of priorities for a sustainable home.

Yet a super-insulated and air-tight home is also a more resilient home. Such a home doesn’t need as large of a heating-and-cooling system, and that system doesn’t need to use as much energy to keep the home at a comfortable temperature.

These homes warm up or cool off more slowly on their own, with less need for energy input. This means that during periods of extended power outages, these homes can keep their humans better sheltered from extreme outdoor temperatures.

- Use sun tempering and natural comfort principles

The shape and orientation of a home also plays a role in how well it can maintain safe and comfortable indoor temperatures.

Passive solar design principles combine with super-insulation to do this to great effect: orienting the largest portion of a home’s window glass toward the sun (and limiting glass on all other sides), using thermal storage materials in the sunny space to hold on to heat gained through the windows while shading or screening devices work to keep that heat out in summer.

The more that passive solar principles are followed, the lower the heating load of the home, yet even modest attention to these design principles can improve a home’s comfort.

In the northern hemisphere, overhangs or awnings should shade most south-facing windows, large north-facing windows should be limited, and designers should avoid placing small rooms with large windows on the south or west to avoid acute overheating.

- Design for drying

Water destroys homes, and it can strike in ways both dramatic and subtle.

Though storm surge, wind-driven rain, and widespread flooding are certainly familiar concerns for those building in hurricane zones, simple and robust practices against water and moisture intrusion should be a high priority in every home design.

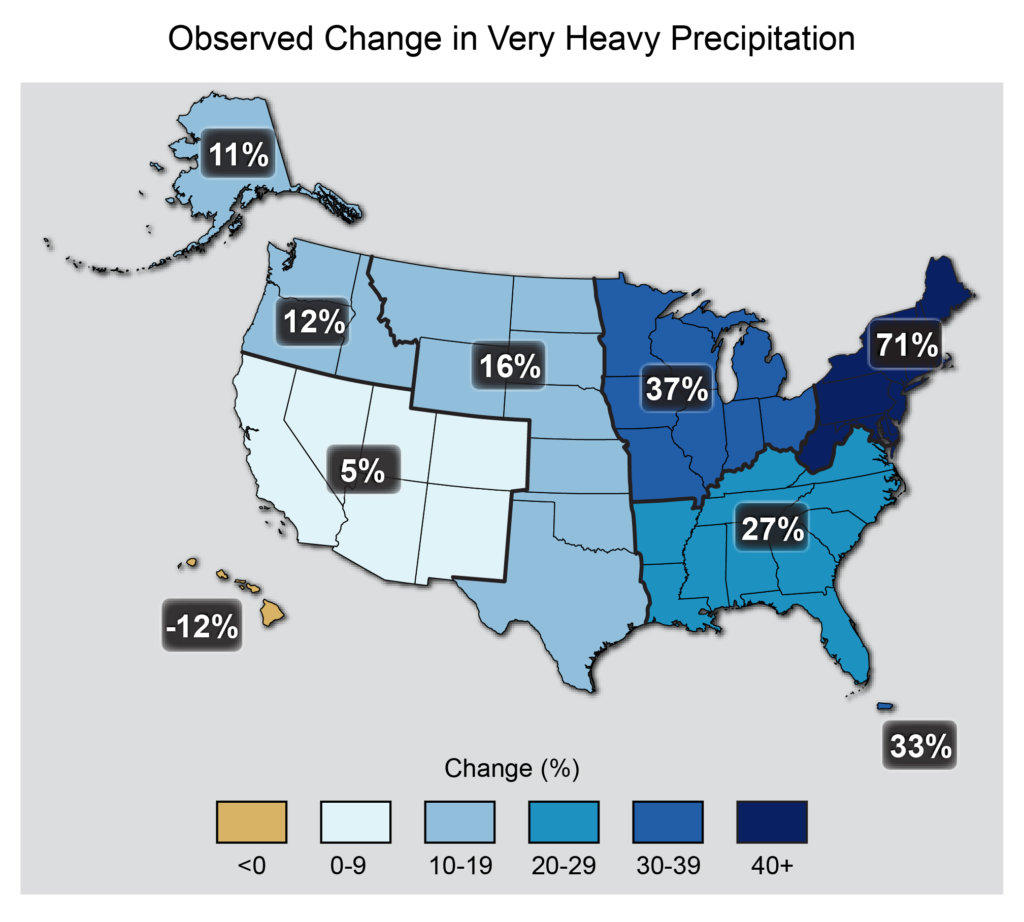

According to climatologists, most regions of the U.S. are seeing dramatic increases in “big rain” events: intense, heavy downpours that dump an increasing proportion of the region’s annual rainfall all at one time, often overwhelming natural and man-made stormwater infrastructure.

In the face of these deluges, design principles for moisture control become more important than ever. Deep overhangs act like an umbrella for the home, directing rainwater away from the walls below. Gutters, downspouts and continuous foundation drains around the perimeter of a home further collect water and direct it away from the home. The layers of materials that go into any exterior wall, roof, foundation or floor should be considered for how they work together to keep water out while also allowing any moisture that does get in anyway to dry back out again. The ENERGY STAR® for Homes Water Management Checklist offers good practical guidance for building moisture out of the structure.

Meanwhile, site and community stormwater management features should be built for the rain that might be seen in historic events, not just commonplace ones. The Green Built Homes Version 3.0 checklist offers great suggestions, including the use of permeable surfaces rather than nonporous ones, and natural stormwater features such as retention ponds, swales, or rain gardens.

- Incorporate regenerative strategies, or plan for their future integration

Regenerative buildings are defined as those that “produce all of their own energy, capture and treat all water, and are also designed and operated to have a net-positive impact on the environment, including repairing surrounding ecosystems.”

While this might be more aspirational than currently feasible for some systems in our homes, some bridge regenerative practices can be nonetheless incorporated into homes today. Meanwhile, other future possibilities can still be affected by how new homes are planned today.

One example would be an all-electric home, with planned-in space for future solar generation and future battery storage. Going all-electric capitalizes on the fact that the largest energy-using systems in a home — heating and cooling, water heating, cooking, clothes drying, and increasingly transportation — have all-electric options that are considerably more energy efficient than alternatives that burn a fossil fuel. (For example, heat pumps and heat pump water heaters are more than 100 percent efficient, while electric induction ranges offer a cooking experience like gas but consume much less energy than gas while also offering better indoor air quality.)

A home’s electricity use, in turn, is increasingly able to be offset by affordable on-site or neighborhood-level solar generation. Meanwhile, the electric grid overall is getting greener: supplying more and more of our electricity from cleaner-burning or renewable energy sources.

The gradual decrease in the cost of batteries will soon make storing energy on site more affordable, providing easier backup in the case of a natural disaster. Yet gains in energy monitoring and load-management technology could even make highly resilient community-level scenarios possible in the future, such as solar microgrids that store excess energy in heat pump water heaters and electric cars batteries, allowing the community to draw on that stored energy in times of need.

This year’s launch of the new and improved Green Built Homes certification will even include a new regenerative designation, recognizing homes that incorporate the best available regenerative elements and technologies — both those that are simple, and those that are more aspirational but nonetheless beneficial. I’m excited to see what new building innovation this spurs in our community, and I hope you are too.

One of my favorite definitions of the term “sustainability” is a simple one: “the ability to exist constantly.” While in the context of green building and environmentalism this often refers to the ability of our ecosystems, our economies, and our very planet to do so, it’s clear that many of these same practices help us sustain ourselves into the future too.

Leigha Dickens is in her tenth year as the green building and sustainability manager with Deltec Homes, a company which specializes in hurricane-resistant homes. She is a member of Green Built Alliance’s Board of Directors, RESNET HERS Rater, and University of North Carolina Asheville alumna of the physics and environmental studies programs. Connect with Leigha at deltechomes.com.

You can also view this article as it was originally published on pages 56-57 of the 2020-2021 edition of the directory.